Barrett’s Oesophagus is when the cells that line the lower part of your oesophagus get damaged by acid and bile travelling upwards from your stomach. Barrett’s Oesophagus is becoming more common in the UK. It’s estimated to affect around two in every 100 people.

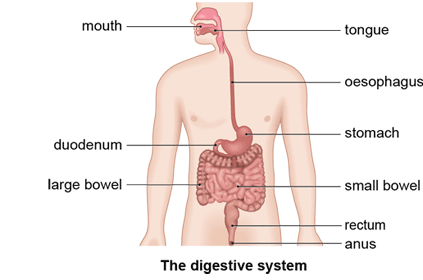

Your oesophagus is part of your digestive system – it’s the tube that goes from your mouth to your stomach. The medical term for acid and bile travelling back up from your stomach is gastro-oesophageal reflux.

You can get Barrett’s oesophagus if you have gastro-oesophageal reflux for a long time – often over five years. Acid and bile that travels up from your stomach may eventually cause the skin-like cells in the lower part of your oesophagus to change. They become more like the cells that line your stomach and small intestine.

Symptoms of Barrett’s Osesophagus

Barrett’s Oesophagus doesn’t cause any symptoms of its own. You may have symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux though, which can trigger Barrett’s oesophagus. These may include:

- heartburn

- indigestion

- food coming back up the wrong way

- difficulty swallowing

If you have heartburn or indigestion, a pharmacist may be able to advise you on treatments that can help. But if your symptoms continue, see your consultant for advice.

Diagnosis of Barrett’s Oesophagus

Your consultant will ask about your symptoms and may examine you. They may also ask you about your medical history.

Your consultant may give you a test called an endoscopy (or a gastroscopy) to look inside your oesophagus and stomach using a narrow, flexible, tube-like telescopic camera. It can help to identify whether your symptoms are related to Barrett’s Oesophagus or another condition. Sometimes your consultant may take a small sample of tissue (a biopsy) from the lining of your oesophagus during the test. They’ll send this to a laboratory to confirm your diagnosis and to check if the cells are abnormal.

Barrett’s Oesophagus is sometimes picked up if you have an endoscopy to investigate another problem, such as tummy pain.

If you’re diagnosed with Barrett’s Oesophagus, your consultant may want to monitor your condition. They’ll arrange for you to have an endoscopy with biopsies at regular intervals. This will help to detect any abnormal changes that may develop in the cells in your oesophagus. You may need to have these check-ups at intervals from anywhere between a few months to five years, depending on how severe your condition is.

It’s not always necessary to monitor Barrett’s Oesophagus in this way. Your doctor will tell you if you need to be monitored and will be able to explain the reasons why.

Self-help for Barrett’s Oesophagus

Your consultant may advise you to make some changes to your lifestyle to help reduce gastro-oesophageal reflux, which may control the condition. For example, they might suggest you:

- lose weight (if you’re overweight)

- stop smoking

- drink less alcohol and coffee

- don’t eat foods that aggravate your symptoms, such as fatty foods – keep a diary so you know which ones do

- eat smaller meals at regular intervals, rather than a large amount in one go

- use an extra pillow or two if you get reflux symptoms at night

Treatment for Barrett’s Oesophagus

Treatments for Barrett’s Oesophagus are targeted at preventing further gastro-oesophageal reflux and, if necessary, removing any damaged areas of tissue from your oesophagus.

Medicines

Your consultant may prescribe you medicines to reduce the amount of stomach acid you produce. This should in turn reduce gastro-oesophageal reflux. They’ll usually prescribe you medicines called proton pump inhibitors. Examples of these include omeprazole, rabeprazole and lansoprazole. You may need to take these medicines long-term to control your symptoms.

Your consultant may prescribe another type of medicine called an H2 receptor blocker, for example ranitidine, to reduce the amount of stomach acid you produce.

Non-surgical treatment

If tests show that your cells are continuing to change, there’s a risk that they may develop into cancer cells. If this happens, you may need further treatment.

Endoscopic treatments include the following:

- Radiofrequency ablation uses heat to destroy the abnormal cells. Your doctor will use a probe to apply an electrical current to the abnormal cells in your oesophagus. This will heat them up until they are destroyed. This is the most common way to treat precancerous cells. See our section on Barrett’s oesophagus and cancer to find out more.

- Endoscopic mucosal resection is a treatment to lift the affected tissue away from the wall of your oesophagus and cut it out. Your doctor may use ablation therapy before or after this, to help get rid of the damaged cells. This technique is often used to remove very early cancer of the oesophagus.

- Photodynamic therapy uses a laser to deliver light energy to destroy the abnormal cells in your oesophagus. You’ll first be given a special medicine, called a photosensitising agent, which makes the abnormal cells sensitive to light.

Your consultant will tell you if any of these treatments are suitable for you.

Surgery

If your consultant thinks you may benefit from surgery, there are two types of surgery for Barrett’s Oesophagus.

Fundoplication

This is an operation to strengthen the valve at the bottom of your oesophagus, which prevents further gastro-oesophageal reflux. In the operation, your surgeon will wrap the top part of your stomach around the bottom end of your oesophagus.

Your consultant may recommend this surgery if your symptoms are really bothering you but you don’t want to take medicines for the rest of your life. It may also be an option if you have side-effects from acid-reducing medicines.

Oesophagectomy

This is an operation to remove the affected area of your oesophagus. Your consultant may advise you to have this operation if you’ve developed an early cancer as a complication of Barrett’s Oesophagus. In this operation, your surgeon will remove the affected section of your oesophagus and then join your stomach to the remaining part.

Barrett’s Oesophagus is caused by long-term reflux of acid and bile. This is when stomach acid and digestive juices travel upwards from your stomach into the lower part of your oesophagus.

Usually, stomach acid is kept in your stomach by a muscular valve that stops it from reaching your oesophagus. But if you have Barrett’s oesophagus, your valve may have become weak or moved out of place, which allows acid to leak upwards. Your stomach is protected from digestive juices by a lining of acid-resistant cells. But the lining of your oesophagus is different, and it can become inflamed and irritated as it tries to protect itself from damage by reflux.

You’re more likely to get gastro-oesophageal reflux if you:

- smoke

- drink alcohol

- eat big meals

- are overweight

- have a hiatus hernia

- are white

- are male

- are over 50

Only about one in 20 people who have reflux go on to develop Barrett’s Osophagus. You’re more likely to develop it if you’ve had severe reflux symptoms for many years.

Complications of Barrett’s Oesophagus

For some people, the constant exposure to acid and bile from gastro-oesophageal reflux over a long period of time causes complications, including:

- ulcers, which can be painful when you swallow food, and if severe, cause blood in your vomit or faeces (which will look black and tar-like)

- scarring of your oesophagus (stricture), which may narrow your oesophagus and make it difficult to swallow

- cancer of the oesophagus

Barrett’s Oesophagus and cancer

Most people with Barrett’s Oesophagus don’t have any serious problems from the condition. But in some people, the changes in the cells that line the oesophagus develop into cancer. This happens to around one or two people in every 20 with Barrett’s Oesophagus. And it usually takes many years or decades for cancer to develop.

During this time, the cells go through a series of pre-cancerous changes called metaplasia and dysplasia. Dysplasia can be labelled low-grade or high-grade, depending on the how much the cells have changed. Cells that have high-grade dysplasia have changed the most, and have the highest risk of turning cancerous.

Not everyone who gets high-grade dysplasia will develop oesophageal cancer. But if you do have these cells, your doctor will monitor you so they can detect and treat any changes in your cells early.